Gold Does Well When the Fed Eases

Gold prices tend to do well around Fed easing cycles. In addition, current inflation concerns and high interest rates make the year-ahead gold return forecast attractive.

Much has been written recently about the impact of bitcoin ETFs (introduced in January of 2024) on investors’ portfolio allocations. The argument goes that ETFs make bitcoin more easily accessible to ordinary investors, and with such easy access will come large portfolio allocations, thus driving up the price of bitcoin. Whatever you think of this argument (a nice summary of different views can be found here), it is hard to argue with the fact that the price of bitcoin has skyrocketed in the weeks after the introduction of bitcoin ETFs.

The above chart shows the spot price of bitcoin over the last three years, along with its hockey stick appreciation thus far in 2024. Alongside bitcoin is plotted the price of gold (the front gold futures contract from COMEX). The bottom chart shows their ratio, i.e., the price of a troy ounce of gold in units of bitcoin. Gold prices, denominated in units of bitcoin, have plunged close to their all-time lows from late 2021.

Taking a step back, many of the arguments investors put forward for why one should allocate to bitcoin also apply to gold. Gold is a store of value which is a good inflation hedge in the long run. Gold is in limited supply (barring major advances in space exploration). Gold is easy to trade because there are multiple liquid ETFs which allow investors to allocate to gold in their brokerage accounts. And should the internet ever go dark (hopefully this will never happen), gold will still sit safely in its vaults, where as bitcoin… Well, you know.

My point in this article is not to philosophize about gold vs. bitcoin as non-dollar stores of value, but rather to point out that the likely start of a Fed easing cycle later in 2024 may serve as a catalyst for the price of gold. For an excellent background article on gold as an investment, take a look at the Erb and Harvey paper. (An interesting tidbit: The paper came out in January of 2013. Since the end of January 2013, the annualized return of IAU — a large and low cost gold ETF — has been a paltry 1.98% per year. During this time, inflation has run at 2.67% per year. In real terms, then, the price of gold has fallen slightly since the publication of the paper.)

Gold and Fed easing

The next figure shows the Fed funds target rate, one of the main instruments of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy, back to the 1970s. The vertical blue lines identify periods of Fed easing, defined as a drop in the Fed funds rate after it had been unchanged for two meetings in a row with a peak fall of over 1.5%.

Based on this definition, the last three easing episodes started in December 2000, August 2007, and June 2019. In all, there were 11 episodes of Fed easing since the 1970s, and gold futures prices are available for 9 of them (gold futures started trading in 1975, so there is no data for the first two episodes). The figure below shows the behavior of gold futures prices in the two-year period prior to and after the start of each easing episode.

Outside of the very minor easing episode that started in 1995, gold futures were either flat or up in the subsequent two years in all cases. Aggregating the performance of gold futures, normalized to start at 100 at the end of the easing month, across all nine episodes shows that, on average, gold futures prices increase by just under 20% in the two-year period after the start of Fed easing. The dark blue line shows the average response, and the lighter blue region around the dark blue line shows the precision with which the average response is estimated. The majority of the response appears to happen in the year after the start of Fed easing.

As of the time of this writing, Fed funds futures are forecasting a start to the Fed easing cycle around July of 2024. Should history repeat itself — never a guarantee — gold may do quite well over the subsequent year or two.

Corroborating evidence

By itself, the event study above may not be enough evidence to make buying gold a compelling trade. The next figure shows the output of QuantStreet’s machine learning based forecasting model for year-ahead gold price appreciation. The blue bar at the left shows the average gold return in the model training window. This is the one-year ahead return — called the unconditional forecast — the model would predict if all forecasting variables were equal to their average values in the training window.

The red and green bars show the adjustment to the unconditional forecast due to the fact that forecasting variables are either above or below their average values in the training window. The be5 variable shows that the currently high level of the 5-year breakeven spread (the difference in yields between nominal Treasuries and TIPS) forecasts gold returns negatively. I interpret this to mean that when inflation expectations are elevated, and they are slightly elevated today, investors buy gold as a hedge, which drives up gold prices, dropping gold’s expected returns.

The dxy_carry variable, which measures the yield differential between 10-year Treasuries and bunds, forecasts gold returns positively. My interpretation is that when U.S. rates are high relative to international rates, it becomes costly for international investors to own gold instead of owning the high-yielding dollar. This drives down the price of gold, thus driving up its expected returns. Currently, U.S. rates are closer to bund rates than they were in the model estimation window, which lowers the gold return forecast.

Finally, gt2 shows that when U.S. 2-year rates are higher than their average value during the training window, as is now the case, next one-year gold returns are on average high. The reason is that, with high domestic rates, U.S. investors may find it costly to hold gold, a zero-yielding asset, thus lowering the demand curve for gold, driving down its price, and driving its expected returns higher.

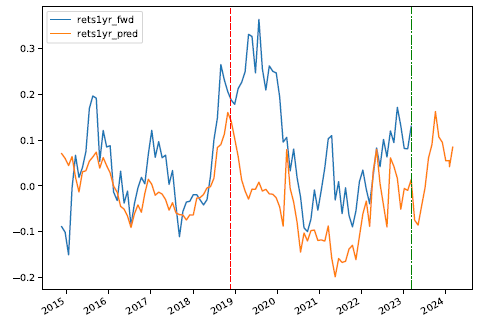

The net effect of these three adjustments is to raise the unconditional one-year ahead gold return forecast to 8.46%. How accurate has the model forecast been historically? The next figure shows the model’s out-of-sample one-year ahead return forecast (the orange line) lined up with the actual year-ahead gold return (the blue line). QuantStreet’s forecasting model has generally worked rather well in this out-of-sample forecasting exercise.

Combining the machine learning forecast with gold’s positive trend over the past year (up over 14%) makes the asset class prospective return look attractive. Furthermore, gold has a low correlation with many risk assets, making it a nice diversifier at a portfolio level. QuantStreet’s asset allocation framework is currently calling for a gold exposure across all risk-targeted portfolios. The potential catalyst of an impending Fed easing cycle is icing on the cake.

Cautionary note and conclusion

Erb and Harvey argue in their paper that one way to normalize the price of gold is to compare it to the inflation price index. If gold maintains its purchasing power in real terms, then the price of gold and the inflation index should move in lockstep. The next figure demonstrates that this did not happen over the last 50 years. After reaching a peak post the inflationary 1970s, the gold futures price divided by the CPI index reached a nadir of 1.4645 in the early 2000s, only to experience a strong subsequent rally into the 6+ range, where it has remained since. Going back to the late 1700s (see Erb and Harvey), the current gold to CPI ratios is extremely high. Were it to mean-revert to its average level of 2 since the 1790s, the return to owning gold would be very negative. On the other hand, as Erb and Harvey point out, this time might be different.

The recent (in historical terms) run-up in the gold price appears to coincide (somewhat) with the introduction of the GLD ETF in November 2004, which made gold investing easily accessible to retail investors. Arguably, the presence of a liquid gold ETF has moved gold valuation permanently into a different regime. (Gold futures have been available since 1975, but it is generally harder to trade futures than ETFs.) Erb and Harvey argue that, by some measures, gold is an underowned asset class and perhaps the presence of liquid gold ETFs have started to chip away at this problem.

On the limited supply side of the story, it is estimated that the total amount of gold that has been mined in the history of humanity amounts to 212,582 tonnes. While no one knows, the best guess is that about 50,000 tonnes are left in the ground. The cost of pulling an ounce of gold out of the ground increased to almost $1,300 in 2022. Finding gold in space is a risk, but at the moment, it is a very remote risk.

To summarize: Gold typically does well when the Fed begins to ease. The net effect of current inflation concerns and high interest rates is to increase the expected year-ahead return on gold. The last-year price trend of gold is positive. Gold is a good diversifier at the portfolio level for most risk assets. Gold is easily accessible to retail investors via several highly liquid ETFs. Gold appears to be underowned and in relatively scarce supply. The negative is that the gold price relative to the CPI index already reflects some of these considerations.

Nevertheless, to me, there is enough here to warrant a tactical allocation to gold in investor portfolios. As always, this allocation should be in line with investors’ risk tolerance and liquidity needs.