International Markets and Rule of Law

Academic work shows that openness, rule of law, and legal protections are associated with investor inflows to global stock markets. Based on such considerations, non-U.S. stocks don't look very good.

Emerging market and non-U.S. developed market stocks have underperformed their U.S. counterparts for the last several decades. There are several potential explanations for this underperformance. First, it is possible that the risk premium for holding U.S. stocks is higher than the risk premium associated with holding international stocks. However, given that U.S. stocks are also considerably less volatile than international stocks, this is unlikely to be the reason.

Another reason might be that capital is not perfectly mobile across countries (i.e., foreign investors either cannot or do not want to own “enough” U.S. stocks), and because of unique local conditions (i.e., a heavily equity-reliant and productive corporate sector), U.S. stocks have structurally higher expected returns than stocks from other countries, despite having lower risk. This is not the focus on my piece, but it does seem like a plausible explanation.

Third, it might be that investors are overly exuberant about the prospects of the U.S. stock market. It is hard to disprove this, but this exuberance has been in place for decades now, and several U.S. stock market crashes (‘99-’01, ‘08-’09 and 2020, for example) have not been enough to undo the effect.

Finally, it might be that relative investing conditions have changed over time to favor the U.S. over other global stock markets, and that investors have been slow to react to this information (consistent with the macro momentum effect documented by AQR and others). While there may yet be other potential explanations, it is this last margin — the relative attractiveness of U.S. markets — that I analyze in this piece.

Impact on capital flows

In his 2015 book, Cracking the Emerging Markets Enigma, Andrew Karolyi analyzes the effects of six country-level risk indicators on the degree to which U.S. residents over- or underinvest in foreign equity markets. In his work, the allocations of U.S. residents to the stock markets of foreign countries, measured in U.S. dollars, comes from the U.S. Treasury International Capital Database as of the end of 2012. The over- or underinvestment is measured relative to the equity market capitalization of a given country divided by the sum of equity market capitalizations of all countries as of the end of 2012. The six indicators used by Karolyi analyze countries’ risk levels are:

market capacity constraints,

operational inefficiencies,

foreign investability restrictions,

corporate opacity,

limits to legal protection, and

political instability.

All these measures are explained in detail in the book. The convention is that higher levels of the variables mean better outcomes (e.g., more openness, fewer restrictions; see pp. 11-12 of the book). Table 10.2 of Karolyi (2015) shows that a one standard deviation increase in the average of these six indicators (meaning fewer constraints, less opacity, and more legal protection — presumably also measured in 2012 — see p. 183) is associated with a 1.24% increase in the relative allocation of U.S. residents’ equity investments to the country in question. Relative to typical over- or underallocations, this is a very large effect. A one standard deviation improvement in legal protections and a one standard deviation drop in political instability are associated with increased relative country allocations of 0.57% and 0.91% respectively. All three effects are statistically significant and economically large.

Table 10.4 of Karolyi (2015) makes a similar point when looking at country-level equity allocations of global institutional investors. Karolyi’s (2005) conclusion is that investor capital tends to flow to countries that open up to foreign investors and that gravitate towards political stability and the rule of law. Aggregating these effects to the stock index level, e.g., all countries or just EM countries, suggests that deterioration in an index’s average score along these dimensions should be associated with investor outflows, and presumably weak index returns for the duration of the outflow episode. Given the fact that capital flows happen slowly, such underperformance could last for long periods of time.

CATO Freedom Index

The CATO Institute publishes an annual study, called the Human Freedom Index, which analyzes country-level economic and personal freedom along 86 dimensions, including:

rule of law,

legal system and property rights,

and an aggregate freedom measure called the human freedom index.

While I do not have access to recent values of Karolyi’s (2015) six risk measures, I assume in what follows that the CATO Institute’s human freedom, rule of law, and legal protections scores are good proxies for Karolyi’s six indicator average, political instability, and limits to legal protections measures respectively.

The next chart shows the human freedom index for some prominent countries currently in the EM index, as well as Russia though it is no longer part of the index. The main takeaway is that many of the large EM economies saw meaningful improvements in their human freedom scores from 2000 until around 2010 — a time-period which aligns closely with EM stock market outperformance seen in the graph above — only to see this trend begin to reverse in the last decade. This deterioration has been much discussed in the financial press, with some arguing that certain EM markets, like China, could become “uninvestable.”

Looking at the major developed market economies, the largest freedom shock over the last two decades was due to COVID-19. As the CATO Human Freedom Index 2023 report states: “The key question in future years is whether governments will fully reverse COVID-related restrictions on freedom as the pandemic moderates or whether some will continue to exert the additional control and spending power they have appropriated to themselves during the pandemic.” Several countries, like Switzerland, the U.K., and the U.S., already show evidence of reversing some of the pandemic-era restrictions, though others, like France, Germany, and Japan have yet to do so.

Based on Karolyi (2015), these trends in developed and emerging market economies do not bode well for international investor interest in global stock markets.

Aggregating openness at the ETF level

To understand how these trends play out in the major global stock market indexes, the next set of charts aggregates country-level Human Freedom Index scores into ETF-level measures using the market capitalization weights of each country in the ETF (see the charts at the end of this article for ETF country weights). ACWI, an ETF tracking the MSCI All Country World Index with roughly a 64% allocation to the U.S. stock market, has the highest aggregate human freedom score, followed by VXUS, Vanguard’s global ex-U.S. stock ETF. The main difference between these is the absence of the U.S. allocation in VXUS, suggesting that the U.S. has a higher average human freedom score relative to the value-weighted score of countries in VXUS. Both the ACWI and VXUS freedom scores fell in 2020 due to COVID-19 restrictions, though the ACWI score has started to bounce back.

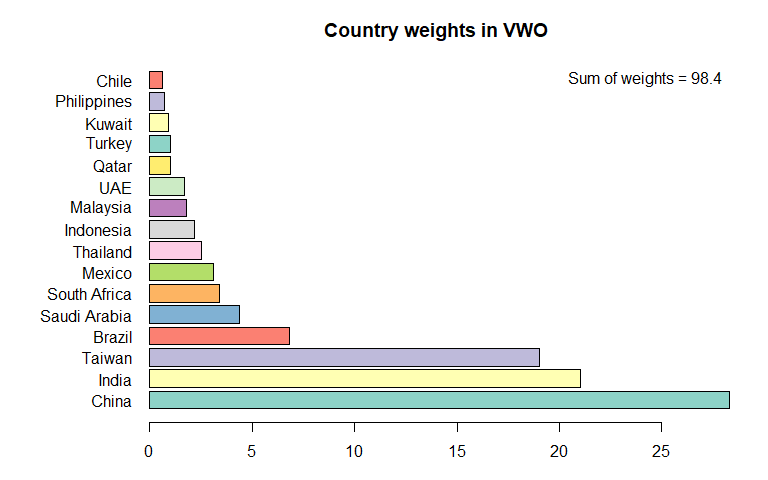

Turning to EM, the VWO ETF (Vanguard’s EM fund) has the lowest aggregate human freedom score. The VWO freedom score has been trending down since its 2007 peak, which neatly coincides with the end of EM outperformance in the mid-aughts. The EM ex-China ETF, whose largest country weights are India, Taiwan, Korea, Brazil and Saudi Arabia, scores higher on its human freedom measure than does VWO, but is still far below the VXUS and ACWI ETFs, which load more heavily on developed markets.

As the next two charts show, the picture when looking at aggregate measures of legal protections and of rule of law are largely similar. Developed markets are well ahead of their emerging market counterparts, and EM ex-China does better than the overall EM index with its heavy China loading.

The trends in the EM legal protections and rule of law scores are negative, reinforcing the takeaway from the main human freedom measure.

Investor takeaways

One of the puzzling market phenomena over the last several decades has been the underperformance of global stock markets relative to the U.S. While there are many potential reasons for this underperformance — some having to do with country-level differences in productivity and innovation which I do not discuss in this piece — one candidate explanation is that non-U.S. stock markets, with a few notable exceptions, are generally less open, and have weaker legal protections and rule of law measures than does the U.S. Karolyi (2015) and other academic work have argued that such openness and legal predictability are important for attracting investor capital and fostering economic growth. The trend in these measures, especially in emerging markets, is not pointing in the right direction, suggesting that future investment returns may well continue to favor U.S. markets, as has been the case for the last several decades.

Country weights in different ETFs

The next several charts show country market capitalization weights in different international and global ETFs. These weights are used to aggregate CATO Human Freedom Index scores into ETF-level measures.

The next chart shows the weights in the EM index.

The next chart shows the weights in the EM ex-China index.

The next chart shows the weights in the global, ex-U.S. stock index.

The next chart shows the weights in the global equity index which includes the U.S.